Another interesting aspect is that we were worried that people might abuse the text with hate-speech of some kind. We put a lot of time and attention into how we were going to monitor and control that. And then what we discovered in doing it because Sam Hill, who wrote the script for all the objects, is a beautiful, charming human and had characterised the objects as naive, playful and adorable objects, that people responded in kind. People would be very sweet to these objects and treat them like toddlers.

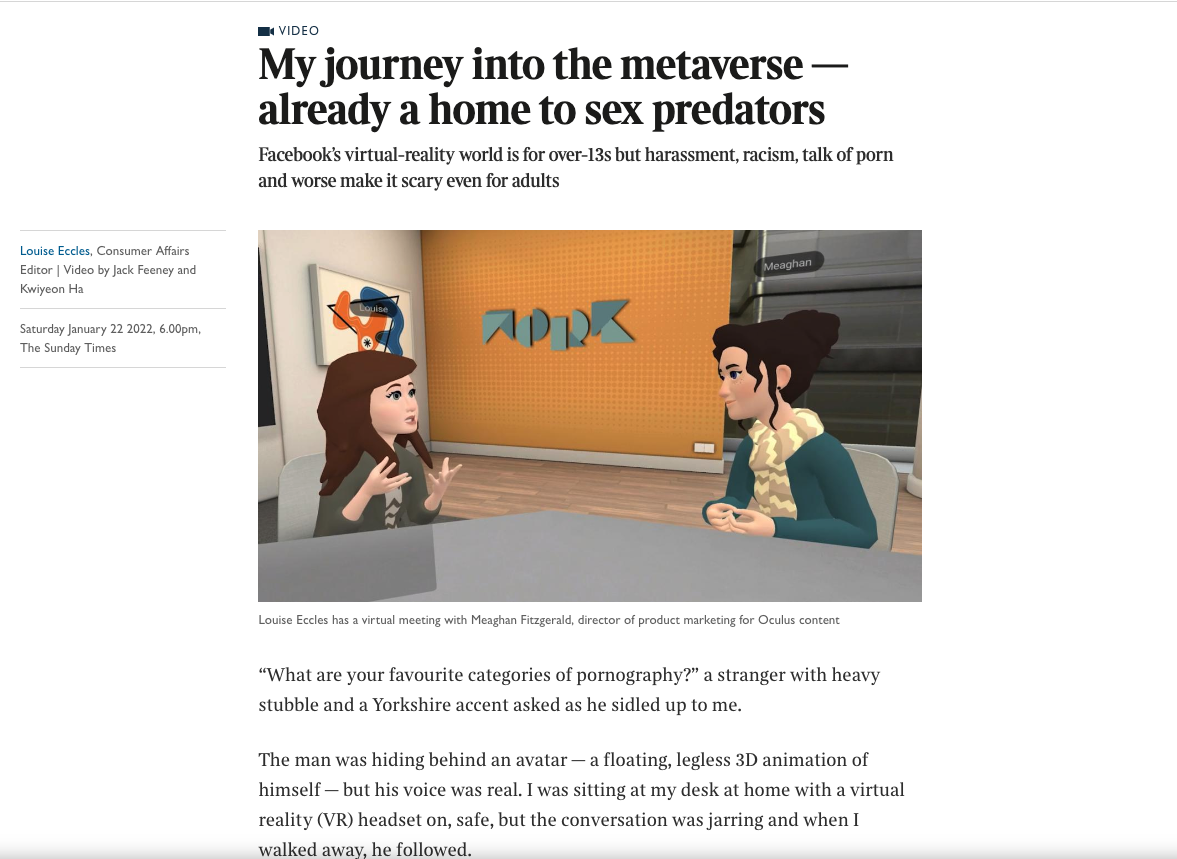

So you can in the design of something, encourage behaviour and you can set the tone for a space. And I think one of the challenges with what we’re seeing in the metaverse is that the tone that’s being set, deliberately or otherwise, is encouraging really specific behaviours. There’s a kind of Wild West libertarianism that’s very anti-difference. This is bringing over certain behaviours from online gaming that might be considered ‘banter’ but which can be experienced quite differently in embodied internet forums. We are seeing quite a lot of harassment in these open, unmoderated VR spaces, particularly when avatars and voices are female-presenting which appears to be quite a an instant trigger for abuse.

There is a limit on how much control a creator can have through the initial design. Metaverse spaces evolve and are co-designed by the people that use them so can we leave it to these communities to self-police? That’s not working well so far. In the material world, public space is notionally maintained by civic authorities and private spaces are maintained by private individuals and they all have obligations around health and safety and legality. If you encounter difficulties, you have some legal recourse. You might assume your civil liberties transfer into digital space, but they don’t. I don’t quite understand how we are where we are now, where if you report an assault in a virtual space. There is no authority that can do anything about that.

There is an organization called the Centre for Countering Digital Hates that makes a point of trying to report those things to the proper authorities. And they just report hundreds and hundreds and never hear anything back because there are not structures in place that can deal with these, not just to look after the victims, but also to make changes and hold different platforms accountable.

Prof Helen Kennedy: Are there other kind of grassroots interventionist projects that you’d want to name check that are doing interesting work in this space?

Verity McIntosh: Nina Salomon’s XRDI do really wonderful work in intersectionality, diversity, inclusion and exclusion in digital technologies. Also XRSI which advocates for representation and safety and things like the right to mental privacy.

One of the issues that is getting closer all the time is that wearable technologies such as virtual reality headsets and controllers give tech companies access to phenomenal amounts of personal behavioural data. That’s one of the reasons Facebook/ Meta are in the game because rather than clicks and likes, they can now access fantastically useful information about where people go, who they meet, what they say, where they look, even what makes their pupils dilate. This incredibly revealing psychometric and biometric data, and is quite harvestable with the current user agreements.

We can talk about our right to be present in a space and to be represented in the democratic system, but actually we’ve never had to defend our subconscious before. Research suggests that our subconscious can be really well interpreted by these devices so the right to mental privacy should be cooked into every piece of legislation.

The IET report is now out which covers quite a lot of this – https://www.theiet.org/safeguarding-the-metaverse

Donna Close: How do we co-create physical and digital spaces of shared humanity through which to inspire a duty of care to each other?

Verity McIntosh: I think one of the challenges in the next 10 years is going to be whether or not there is a sort of an open Internet version of data layers or if they will be quite heavily gate-keepered through proprietary software

Currently people are bonded to specific devices and specific publishing platforms so it’s quite challenging already for people who sit outside of the expected terms and conditions of that to make work. For example, some app stores are banning any form of nudity or sexual content for morality reasons, but it’s really inhibiting what artists might want to create for these platforms and presuming that there’s a sort of immodesty agenda. So yeah, some sort of open addressable framework that is much more born of the 80s and early 90s approach to the Internet – that everybody has an equal right to publish at no cost point, and to express a range of opinions. That would be great.

Skills are such an important part of this too – the arts community are amazing polymaths and an incredibly versatile community who will always seek to explore how the dominant technologies of the moment can problematized, unpacked and held up to the light. For lots of reasons, it’s really hard to do that with the metaverse. There’s a presumed high learning curve to get to grips with some of the foundational technologies. It’s not mega easy to prototype using these tools. It’s not terribly easy to get stuff to an audience just to try things out. I think it’s really troubling how much the opportunity to engage with these things currently manifest as hack days and at weekends with middle class white men who are able to spend a weekend doing a games jam.

There are lots of amazing people who are being cut out of the conversation and of that process.

It takes effort to make space for people who have more complex lives. If it doesn’t happen now, then we’ll have to battle it back later. There are a few of us, yourselves included, who are trying to take on that challenge and come up with pathways in because, once people have a little hook in it gets easier. Access to basic technologies and some fundamental skills training is really hard to come by and it needs to be easier.

It wasn’t that long ago that the ability to code was suddenly understood to be a really valuable tool but only available to certain disciplines and that’s cooked in much earlier into secondary school education. Younger students are much more confident – they often know some HTML, they may know about coding and have a grounding in digital media literacy. Older people won’t necessarily have had the same basic technology skills and foundation modules in these are hard to come by. We need the same approach to support the next generation to engage skillfully and critically with the Metaverse.

It also feels really important that teachers and parents have access to robust information in order to help children negotiate these spaces so there’s a whole there’s a whole process of upskilling that needs to happens now.